Trees: Risks, Rights & Responsibilities

Our responsibilities with regard to trees is a two-way thing; tree owners and managers have a duty of care to ensure they don't give rise to unacceptable risk or excessive nuisance to others; on the other hand we have a duty of 'environmental stewardship', to protect and nurture trees and so foster the myriad benefits they provide, from purifying the air we breathe and locking in carbon to offering shelter and sustenance for countless species and mitigating flash flooding. Beyond these tangible benefits, trees contribute to our well-being, offering aesthetic beauty, shade, and a sense of peace. Nevertheless, any perceived risk from a tree is routinely seen as outweighing the benefits that it might provide. It is vital that we fully understand the true level of risk posed by any tree in order that its management strikes a sensible balance between these positive and negative factors.

See also 'TREES & BUILDINGS' & pages on 'DAMAGE CAUSED BY TREES' & 'TREE-RELATED SUBSIDENCE'

Risks from Trees

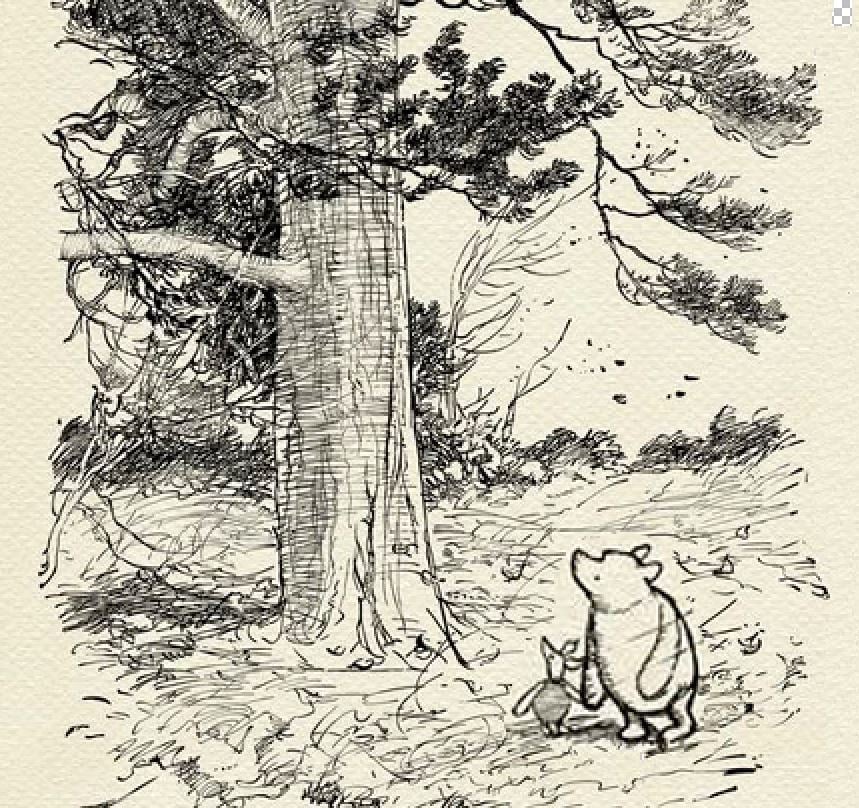

"Supposing a tree fell down, Pooh, when

we were underneath it?" said Piglet.

After careful thought, Pooh said

"Supposing it didn't,"

Piglet was comforted by this.

The chances of winning the National lottery (Lotto) jackpot are about 1 in 45,000,000. However, most people who play buy tickets fairly regularly and if you play just once a month, then over a year those odds are reduced to 1 in 7,500,000. On the other hand about 6 people are killed each year as a result of a tree failure which, amongst a population of 66 million means that the chances of being killed by a tree are about 1 in 11,000,000. So you’re considerably more likely to win the Lotto jackpot than be killed by a tree! In fact trees are well down in the league table of causes of accidental death, as is shown in the following table, which compares the numbers of annual deaths from a number of causes with the level of risk, the calculations based on the current population of the UK.

Causes of death | Approximate number | Annual | Source of statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

Accidents at Home | 6,000 | 1 in 11,000 | RoSPA |

Road traffic accidents | 1,695 (2022) | 1 in 39,000 | Police statistics |

Murder* | 583 (2023/24) | 1 in 112,000 | ONS (Office for |

Accidents at Work | 18 (2023/24) | 1 in 496,000 | HSE |

Falling Trees & Branches | 4.5 | 1 in 11,000,000 | NTSG |

Lightning | 2 | 1 in 33,500,000 | https://tinyurl.com/5b3nbu66 |

* Clearly Murder should not be counted as an 'accident'; it's just included for comparison!

As for non-fatal injuries, hospitals report about 55 admissions to A&E units annually as a result of being struck by a tree or a part of a trees. This compares to some 2.9 million cases of ‘leisure-related’ admissions; these include 262,000 injuries sustained while playing football; 10,900 recorded annually as being caused by children’s swings and some 2,200 that were caused by wheelie bins!

The point is that trees are much safer than most people think. This is not surprising when you consider that they’ve been evolving over millions of years to end up with structures that are generally capable of withstanding nearly all the conditions that nature throws at them. Indeed tests have shown that the ‘safety factor’ of an undefective tree is in the region of 4.5. In essence, this means that it’s four and a half times stronger than it needs to be in order withstand all conditions that it’s liable to be subjected to under normal circumstances. This is similar to the safety factors that engineers aim to build into man-made structures such as buildings and bridges.

Even so, just as man-made structures do sometimes fail, the same can apply to trees. In practice, most storm failures are associated with pre-existing structural defects in the tree (many of them the result of what people have done to them in the past). But even so, exceptionally windy conditions can result in a structurally ‘perfect’ specimen being damaged or even blown over. It is nonetheless important to appreciate that the general level of risk posed by trees is low.

However, while there’s really no point in losing sleep over such a low level of risk, it's clearly sensible for those responsible for trees on their property to take reasonable precautions to ensure the trees are in acceptable condition and that they don't pose a significant danger to person or property.

National Tree Safety Group

Thw NATIONAL TREE SAFETY GROUP (NTSG) has produced a detailed report on the risk management of trees. A summary of its findings is available by clicking on the image on the right; the full report can be downloaded HERE.

What is a 'dangerous' tree?

The risk posed by a tree cannot simply be assessed by the presence of structural fault such as a zone of decay or a split branch; indeed the identification of a ‘defect’ does not tell us anything about the actual risk that it represents to person or property. In order to make a realistic risk assessment one needs to consider three distinct aspects of the situation, namely:

1) What is the 'Target Potential'? What is the likelihood that the failure of a tree or a part of one will actually hit someone , or strike something of value?

2) What is the 'Impact potential'? If that failure were to occur, how much damage would it be capable of causing? Essentially, how big is the part at risk of failure?

and 3) What is the Likelihood of Failure? What is the realistic probability that the split branch, the decayed limb or other part at risk, will actually break in the foreseeable future).

There are subjective elements to each of these factors, but only by considering all of the them can one come up with an informed assessment of the risk associated with any given hazard and determine what, if anything, should be done to mitigate that risk.

When considering the degree of risk that a tree might represent, the importance of the question as to whether someone or something (a ‘target’) is actually likely to be present under the tree at the moment a failure occurs is often under-appreciated. Targets such as buildings and parked cars may be present in the potential ’fall zone’ permanently or for extended periods, but when one considers the length of time that a moving vehicle or a pedestrian is in that area, this frequently amounts to no more than a matter of seconds. Furthermore, tree failure can occur at any time of the day or night throughout the year and for much of that time the frequency of occupation may be negligible.

Other factors also come into play, such as the vulnerability of a target to damage: a pedestrian or cyclist is highly vulnerable; the occupant of a building much less so. Traffic speed may also be relevant, for while a car travelling at high speed will be in the ‘danger zone’ for a very short time, it could also suffer as a result of striking (or indeed avoiding) fallen debris on the road. On the opposite side of the equation, while tree failures are more likely to occur in stormy conditions, site usage rates, particularly by pedestrians, will be reduced at times of bad weather.

It's estimated that there are about 3 billion trees in the UK and the vast majority don't fail, but even when one of that 3 billion does fail, the likelihood that it will result in serious harm is actually very small. The takeaway point is that while the risks posed by trees should never be wholly disregarded, the level of safety that a situation demands must be set within the context of its environment. The risks associated with a tree in the open countryside may be so small as to be truly negligible and its ‘defects’ may simply be regarded as additional wildlife habitat. But even where the risks of harm are not negligible, they should be carefully assessed in relation to the degree of risk. A tree in in a quiet side street or in a garden at some distance from any building will still require considerably less stringent safety margins than would one growing in a town centre or alongside a busy road.

Leaning Trees

Are leaning trees dangerous? Or rather are they more dangerous than one that is more or less vertical and in balance.

The short answer is no, provided the lean is 'natural', which is to say that it is a characteristic that the tree has grown up with over the years and is not something that has formed recently.

Trees will often develop unbalanced or leaning forms as, for instance, is often seen in trees in exposed situations on mountains and by the coast, as in the image on the right. They will also frequently grow more on one side that the other in response to being shaded, as frequently occurs with trees growing on the outer edge of woodland, or just amongst a small group of close-growing trees.

Of course it does take more strength to keep a leaning or unbalanced structure from toppling and in leaning trees the additional strength needed is provided by the uneven development of tissues across the plane of the lean: thus it's generally found that there are wider annual rings on one side of the leaning stem than on the other, while the tree's root system will also tend to develop preferentially on the tension side (i.e. opposite the direction of lean) in order to more effectively oppose forces tending to cause it to topple.

Thus generally speaking, trees with a long-standing and non-progressive lean are unlikely to be any more hazardous than a more vertical, upright one. Nevertheless, leaning trees will be more susceptible to changes in their surrounding and to factors affecting their strength and integrity. For instance, the removal of trees nearby could lead to increased wind exposure which could result in increased risk of failure; decay or damage to the lower stem will tend to affect stability sooner than might be the case in a vertical tree, while decay or physical damage of the root system could also increase the likelihood of failure. Other factors that might affect leaning trees more than upright ones include reduced roothold due to soil disturbance or waterlogging, as well as increased loading, such as as may result from heavy snowfall.

When a tree does begin to uproot it will nearly always be the case that any increase in lean will result in the soil being lifted on the opposite side to the lean, due to the stiff, woody roots that generally radiate out from the trunk (the 'rootplate') being tipped upwards.

But how do you tell if a lean is become progressively greater? One simple way to tell is to fix a nail on the side facing the lean, at some distance above ground level, say at about 1.5 to 2 m. You can then attach a plumb-bob to the end of the nail and note were it comes to rest just above ground level. Mark that point in some way, for instance with a small stake driven into the ground. You can then re-attach the plumb-bob at intervals and see if it settles over the same point. If not, if it comes to rest further out, that would indicate some movement in the tree, in which case, if there is some risk of failure causing harm or damage, some action may be advisable. However, it is also worth noting that it is by no means unknown for a tree that has shifted in the ground , for instance as a result of a storm, to re-establish its roothold and settle in its new position.