Veteran & Ancient Trees

Ancient trees are amongst the largest and oldest living organisms on the Earth; they are of immense ecological and scientific significance as well being of historical and cultural value, having inspired folklore, legends and art. Being features of the landscape that date back hundreds of years they inform us of the traditional practices of woodland management such as coppicing, pollard management, providing evidence of cultural heritage and land use patterns of former centuries

The United Kingdom has about 13% tree cover compared to about 37% for Europe as a whole; yet something like 80% of all ancient trees in Europe are in this country. In fact, you would probably have to travel to southern Europe, to Portugal, Spain or Greece to find anything that is of comparable age to trees such as the Ankerwycke Yew in Berkshire, the Tortworth Chestnut in Gloucestershire or Herefordshire’s own Jack o’ Kent’s oak, (illustrated above), just one of many important ancient trees in the county.

Ancient trees connect us to our past, reminding us of the rich history of our landscapes and conferring a sense of identity and cohesion on a place and a people. But more than that, they are of immeasurable importance ecologically. Their cavities and hollows, their dead and decaying wood, their sap-runs and water pools provide a range of habitats that support an enormous variety of fungi, plants and invertebrates, providing a repository of genetic information from many centuries past.

The Woodland Trust has recently published revised guidance on Recognising Ancient And Veteran Trees. It includes a one-page key, designed to aid the recognition and categorisation of Ancient & Veteran trees, along with comprehensive guidance on their distinguishing characteristics and significance alongside more comprehensive guidance .

In recognition of the importance of these trees, The Ancient Tree Forum was founded in 1993 with the intention of raising awareness of them in order to protect them and to improve their management.

Find out more at the ATF website - click HERE

Also, Click HERE for an ATF LEAFLET that includes QR codes to provide links to their training and events programme.

In order to protect ancient trees it is clearly vital to know where they are and with this in mind the Woodland Trust began a project in 2006 known as the Ancient Tree Inventory. This aims to map all of the ancient and veteran trees across the United Kingdom. So far over 200,000 of the nation’s oldest trees have been recorded, their locations and details being freely available on the ATI map, which can be accessed HERE (or click on the logo on the left).

But there are still many veteran and ancient trees to record; anyone can add a tree to the inventory - see HERE.

How old does a tree have to be to be 'Ancient'?

Ancient trees can simply be defined as a tree that has survived considerably longer than most others of its species. However the life expectancies of different species vary widely. There’s an old forester’s proverb that says great oaks take 300 years to grow, 300 years to stay, and 300 years to die. By no means do all oak trees live for 900 years or more, but it would be reasonable to assume that an oak that’s more than about 500 years old can be regarded as ‘ancient’.

In contrast, trees such as birch and willow have more of a ‘live fast, die young’ philosophy, generally having life expectancies more like 50 to 70 years. However some do live considerably longer; but while an oak of 100-120 years is just a youngster, a birch or willow of that age could well be regarded as Ancient.

For a tree to be ancient it must by definition be significantly older than most other trees of the same species. What then is a ‘veteran’ tree?

Essentially, it is a tree that shows features that are characteristic of ancient trees, such as decay, dead wood rot-holes and so on, all of which provide increased value to wildlife, but which are not necessarily old enough to be classed as ‘ancient’. All ancient trees are veteran trees, but not all veteran trees are old enough to be ancient.

What, then, is a 'Veteran' tree'?

If to be ancient a tree must by definition be significantly older than most other trees of the same species, what then is a ‘veteran’ tree?

Essentially, it is a tree that shows features that are characteristic of ancient trees, such as decay, dead wood rot-holes and so on, all of which provide increased value to wildlife, but which are not necessarily old enough to be classed as ‘ancient’.

All ancient trees are veteran trees, but not all veteran trees are old enough to be ancient.

How to Recognize Ancient and Veteran Trees

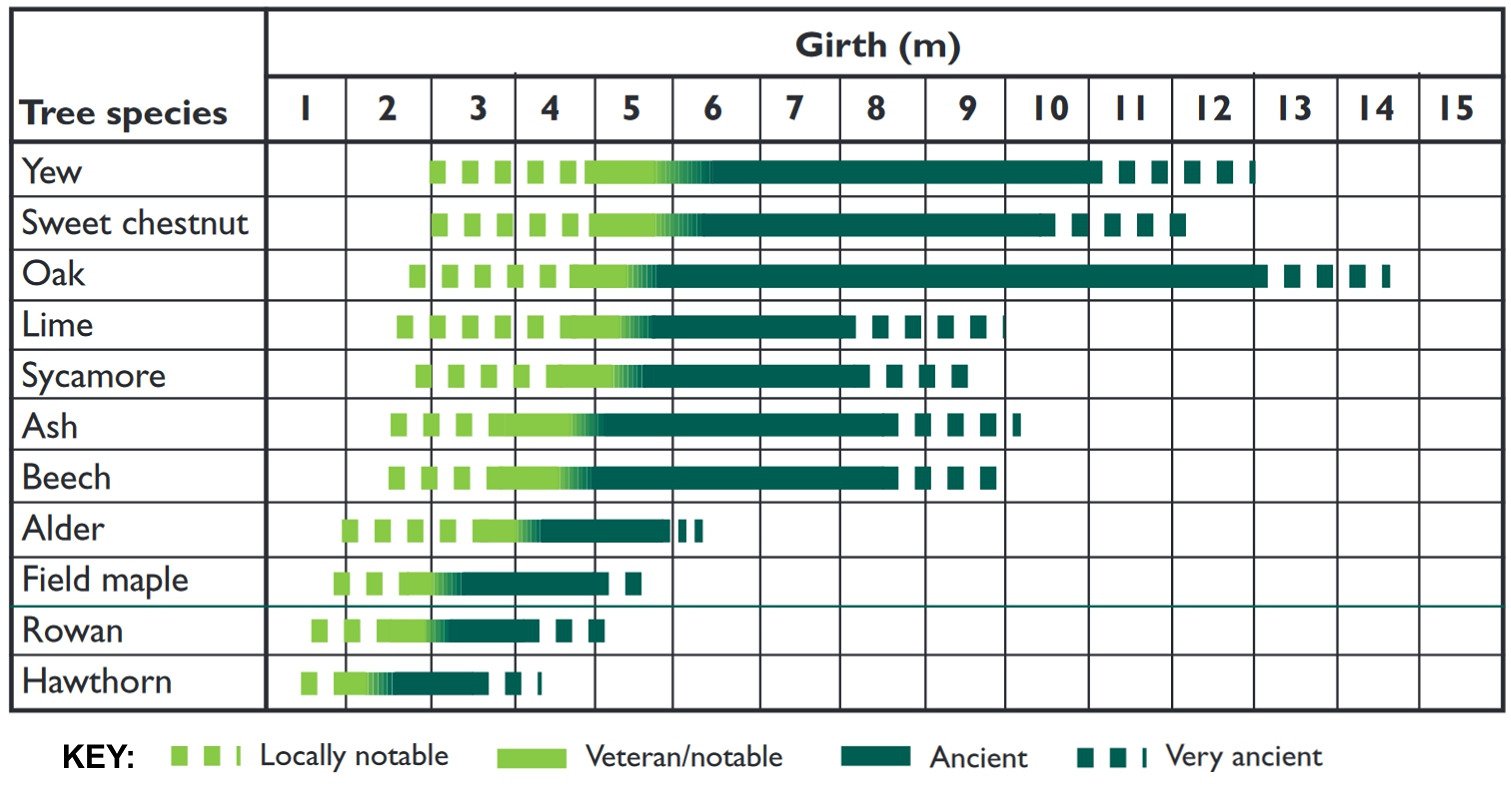

As trees get older, they get larger; at least they get fatter as a result of the accumulation of annual rings. Thus, the girth of a tree, the measurement of its circumference, can be used as a guide to its age. There is of course great variability on growth rates due to the conditions in which the tree is growing, but the table below provides a rough guide as to the relationship between girth of a tree and its life-stage for a number of species

How trees Age

However it’s not just trunk size that makes veteran and ancient tree special; rather it’s the features that develop as a tree passes through maturity towards old age that give it special value.

‘Maturity’ in a tree may be defined as the period when it is approaching full height and growth is slowing. From here it may advance into ‘late-maturity’, characterised by generally reduced vitality and little if any increase in height. Natural branch loss may occur and there is likely to be an increase in the development of deadwood along with localised decay and cavity formation

As the tree edges into old age decay and hollowing of the trunk is likely to occur. Dieback of the upper crown may continue, so as to leave the tree stag-headed, with dead branches protruding above the inner or lower crown which may remain relatively dense. This progressive reduction in crown size, so-called ‘crown retrenchment’, is sometimes referred to as ‘growing down’.

John White of the Forestry Commission has developed a system for assessing the age of trees based on their varying rates of increasing girth at different stages of their lives. It cannot be regarded as providing incontrovertible evidence of age as so many variable factors are involved, but it gives a very useful guide to the age of many species of trees based on their girths. The system is described HERE; it involves a number of stages but a much simpler version has been developed and is published on the Bristol Tree Forum's website which simply requires entering the tree species and girth or diameterr.

Many of our oldest trees have been 'pollarded' at some point in their history by having had their upper parts removed, resulting in new the growth developing from the ‘pollard point’. This gives rise to a new form, recognisable in old trees by which have numerous branches arising from the same point.

In some cases this may be the result of 'natural' pollarding, where the top of a tree was lost due to a cause such as storm damag. However, most pollarded trees are the result of historic tree management practice, the trees having been cut back in order to stimulate vigorous regrowth which in due course could be harvested to provide a wide range of produce, ranging from animal fodder (‘pollard hay’), fuelwood (including charcoal) and small-diameter timber for building, fencing and other purposes. In order to prevent the new growth being browsed off by deer and farm animals, the trees would be cut above browsing height, usually at about 2-3 metres.

Pollarding would be carried out at intervals that depended on the intended produce; perhaps every 2 to 6 for fodder, when it would result in an abundance of leafy material, but at longer intervals of 8 to 18 or even more years to produce material for charcoal or poles for fencing or construction. However, by removing the top growth the trees would be maintained in a partially juvenile, vigorous state while also being much less liable to storm damage. As a result they could persist in growth almost indefinitely, their trunks (or boles) becoming ever larger in diameter and very frequently becoming hollow. However the practice of regular pollarding declined and largely ceased 100-200 years ago. As a result there are many veteran and ancient trees which are ‘lapsed pollards’ with large, often hollow boles with most of the branches arising from around the original pollard point but which, had they not been pollarded in the past would almost certainly not have survived. One such is the Great Oak of Eardisley, illustrated below.

Lapsed pollards, with heavy boughs supported on potentially fragile hollow boles, require careful management to ensure that the weight of the growing branches doesn't cause the trees to break up and collapse. Such weight reduction will inevitably involve the removal of part of the tree's crown, so with ancient trees, which lack the vigour of young specimens, pruning may have to be carefully phased to ensure that the tree retains sufficient foliage to keep it in healthy growth.

The Importance of Veteran and Ancient trees for Wildlife

The features that characterise veteran and ancient trees, including dead limbs, , decayed and decaying wood, hollows and rot holes, water pools, seepages, splits and loose bark, all provide valuable habitats that are rarely found on younger trees. They are also home to many epiphytes (plants that grow on other, larger plants) as well as being host to a diverse and luxuriant growth of bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) including rare species, such as specialist mosses that live in the periodically wet spots below the opening of rot holes.

Old trees with their hollows and cavities provide nesting and roosting sites for birds such as owls, kestrels, marsh tits; treecreepers commonly nest under loose bark while woodpeckers and nuthatches excavate partly-decayed wood to create their own nest holes.

Decaying wood is also incredibly important for invertebrates: around 1,700 invertebrate species in the UK need decaying wood at some point during their life cycles, including some 650 different species of beetle, such as those illustrated below. (Click HERE for more information about beetles and dead wood).

Different invertebrates prefer decaying wood at different stages, some prefer the decay of certain trees, and others rely on the kinds of fungi living on dead wood, with ancient and veteran trees hosting the widest number of species.

Veteran Trees: the Law and Planning

Despite their undoubted significance ancient and veteran trees have no automatic right of protection; . some individual trees may be covered by Tree Preservation Orders, but at the time of writing the great majority have no legal protection. Early in 2024 the Heritage Trees Bill was introduced in The Lords with the intention of allowing important veteran and ancient trees similar protection to that provided to important archaeological sites when they are designated as Scheduled Ancient Monuments. However the bill proceeded no further than its first reading and, since the election, is effectively defunct, leaving the vast majority of ancient trees with no protection under the law.

The planning system, however, does allow local planning authorities to give some protection where proposed development sites abut ancient woodland or where veteran trees are present. In these circumstances the local authority should adhere to government guidance as contained within the document Ancient woodland, ancient trees and veteran trees: advice for making planning decisions

This recommends that planning authorities should refuse planning permission ‘if development will result in the loss or deterioration of ancient woodland, ancient trees and veteran trees, unless (a) there are wholly exceptional reasons and (b) there is a suitable compensation strategy in place’

‘Suitable compensation’ should include mitigation measures in the form of buffer zones, more generally known as root protection areas (RPAs) within which no disturbance as a result of construction activity should be permitted.

For most trees (i.e. non-veterans) the RPA is based on the area of a circle with a radius of 12 times the trunk diameter of the tree, measured at 1.5m from ground level. This area is capped at a maximum of 707 sq. m (equivalent to a circle with a radius of 15m). However ancient and veteran trees are likely to have larger rooting areas and to be generally more sensitive to disturbance of the rooting environment so that RPAs calculated in this way are likely to be insufficient to ensure adequate protection.

Thus for veteran and ancient trees the buffer zone should have a radius of at least 15 times the diameter of the tree. For example, a veteran tree with a diameter of 80cm (girth 2.5m) should have a buffer zone of at least 12m, while one of diameter 1.2m should have an 18m buffer zone. Sometimes it may be the case that the canopy of the tree spreads further than 15 times the trunk diameter, in which case the protection area should be extended to at least 5m beyond the edge of the canopy.

The guidance document also states that similar recommendations should apply to veteran trees growing on or near the boundary of an area of ancient woodland. However even if individual veteran trees are not present, the wider environment of ancient woodland should be protected by the establishment of a buffer zone boundary that extends to 15m beyond the woodland boundary.